Note-Taking: A Guide for Undergrads

- John H Keess

- May 21, 2020

- 3 min read

This post is meant to be a quick survey of how *I* take history notes. There are many ways of doing it, but I find this works best for me. If you want to really do down a deep, dark, unhappy hole of study habits, see my post on comps here.

Before I begin, I should state that notes should be as short as possible, to force you to rely on your memory. After all, the information only really synthesises in your head, so your notes should, at most cue you onto the information. If you’re new to a topic, they have to be a bit more extensive. For this example, I’ll be looking at the Battle of the Scheldt by studying two books – Jack Granatstein Canada’s Army and Terry Copp’s Fields of Fire.

If I’m studying military history, the first thing I do is to find a map. I’ll usually look in the scholarly sources first to see if they have maps, then use those maps to confirm what I find on a Google image search. Wikipedia generally has contributors who go through the time to pull maps from official histories, which makes stuff easier, but be careful – well-travelled Wikipedia articles can be generally reliable, but lesser-travelled ones aren’t. I’ve found very basic factual errors on Wikipedia. A better place to start is the Canadian Encyclopedia.

After printing the map out, I mark it up. I’ll highlight key areas or write them out in big marker - in this case, the city of Antwerp, Walcheren Island, and South Beveland. I’ll also mark up with big map symbols where the largest formations are. In this case, because divisions moved all around each other, I simply mark the divisions below the corps. The 4th Canadian Armoured Division served with both corps, so it gets tucked in the corner for reference. I’ll go back to this map and mark it up as I read through.

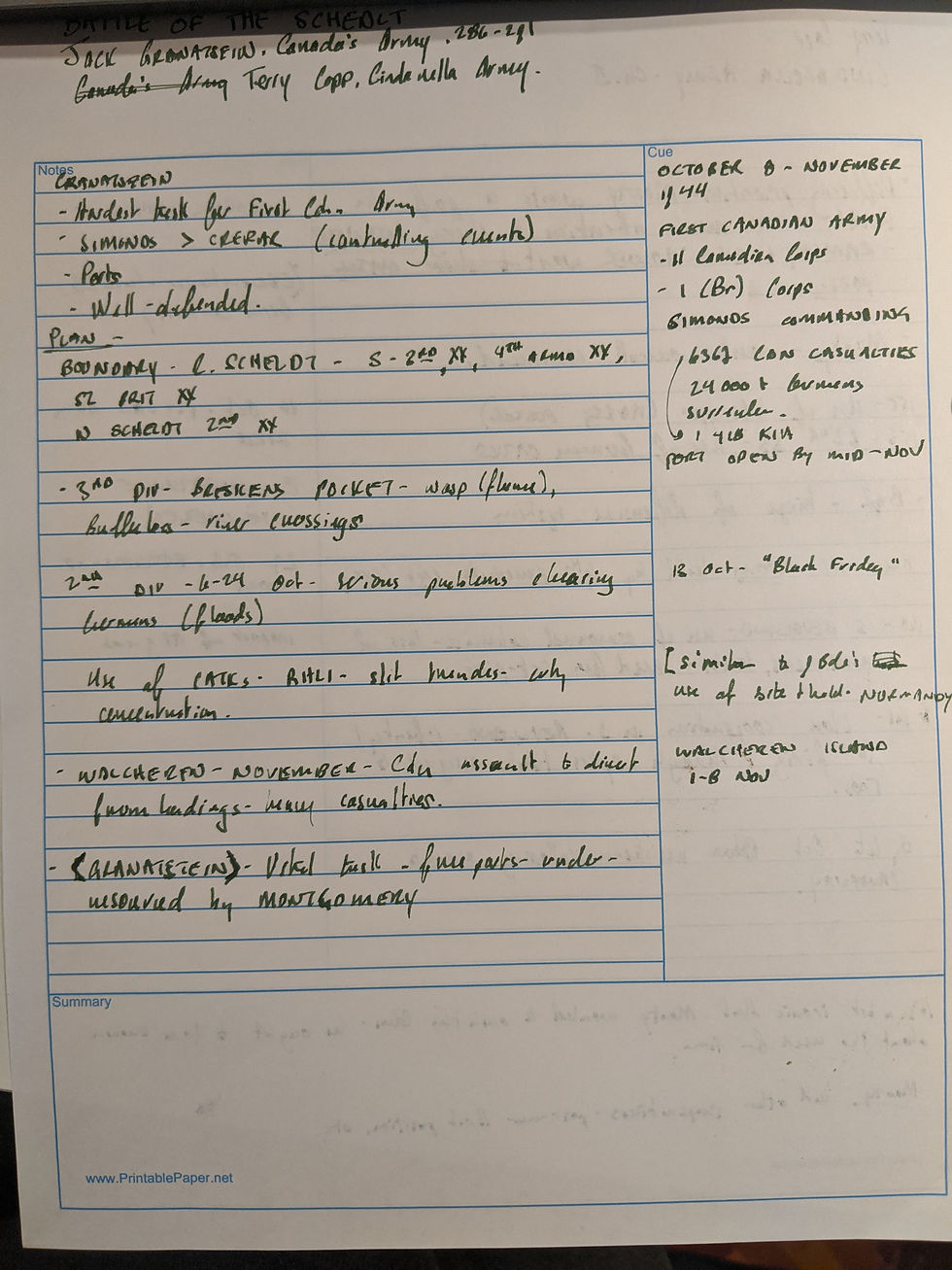

Next I’ll set up my notes page. I like using the Cornell notes system, and I print out formats from printablepaper.net. In the top right corner, I list vital statistics including, dates, a rough order of battle, and casualties. I’ll update this little info box as I go through.

As for readings, I start broad. Something like Canada’s Army is great, because it gives you the “handrails” to guide your way through something. If you’re really new to something, I recommend an article from the Canadian Encyclopedia – they’re all well-written and qualified historians write them. The key is to try to refrain from writing anything down until you can’t take any more information in – try to make it at least to the bottom of the page, but ideally aim for writing every four pages or so. Write in shorthand – I use NATO map symbols to make it all a bit faster – i.e. “9 Cdn X” instead of the “9th Canadian Brigade”. I also use <pointy brackets> to capture the historians’ opinion while I use [square brackets] to capture mine.

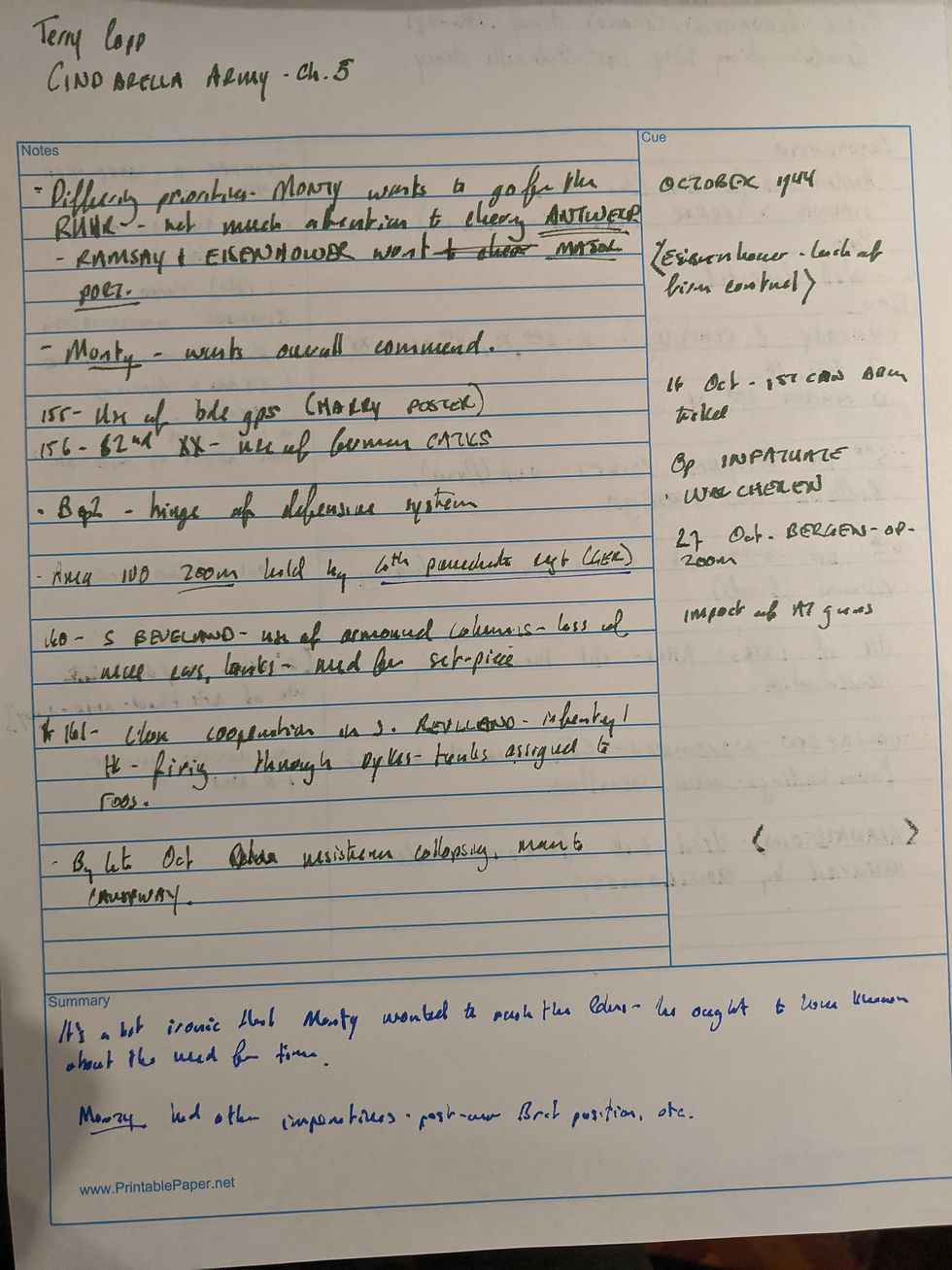

After doing my general reading, I get into the more specific reading. This should build on the more general stuff and add detail. You can see here that my notes are designed to cue me back to the text – Copp writes about the effects of combat stress, so I just need to remember his very general point (the rate of battle exhaustion increased during the battle, partially due to bad conditions) and know that I can always go back to Copp if a I need more detail. I also use the cue bar on the right to note dates and names as I go through the text.

If I can, I’ll sit on it for 24 hours, go over them, reference back to the readings in areas where I’m not entirely sure I can remember the relevant details, then write a quick impression on the bottom.

Comments